Tor.com comics blogger Tim Callahan has dedicated the next twelve months to a reread of all of the major Alan Moore comics (and plenty of minor ones as well). Each week he will provide commentary on what he’s been reading. Welcome to the sixth installment.

In previous installments, I’ve broken down my reread by issue number, or by short story title, and explored my reactions to discrete chunks of narrative. Partly, that was a way to narrow the focus, and pay attention to details, but mainly that approach was a function of the kinds of Alan Moore comics I was writing about. Neither Marvelman/Miracleman nor the Moore-written Star Wars shorts are currently in print, and I’ll admit to a sense of obligation to provide a bit more plot information on the micro scale. It was my way of saying, “hey, you might never have read these comics, but here’s what’s going on, here’s what they’re about, and here’s what’s interesting about them.”

Really, though, the reason I liked the idea of calling this series “The Great Alan Moore Reread” was that it might grow into more of a communal activity. A chance for everyone out there to reread (or maybe read for the first time) these landmark comics written by the guy who is the most universally-acclaimed comic book writer in history. Some of them may not be as good as the others, but that’s something we can all discuss. After all, it’s not Alan Moore that the word “Great” refers to, it’s the size of the reread. (Okay, maybe it’s both. You be the judge.)

So while it may be true that some of the upcoming entries may hover around less-available Moore works (Skizz, for example), starting this week, we’ll be getting into the comics that are easy to find, often in multiple formats. Read along. Reread along. Whatever. And add your thoughts, your perspective, in the comments. Let’s see if we can turn “The Great Alan Moore Reread” into even more than that. Into a virtual “Alan Moore Symposium.” Or to, at the very least, “The Vast and Amazing and Insightful Alan Moore Dialogues.”

This week we’ll tackle the first five issues of V for Vendetta. I’m not going issue-by-issue, but holistically. I’ll highlight what interests me, and provide a bit of context around everything else. And we’ll see what we see.

For this reread, I used the Absolute Edition, but the content of the trade paperback version is almost identical, though the pages are a bit smaller, and I believe an irrelevant (non-David Lloyd-drawn) silent mini-chapter is included in the Absolute edition but omitted from other collections. Read along. Offer your own reactions.

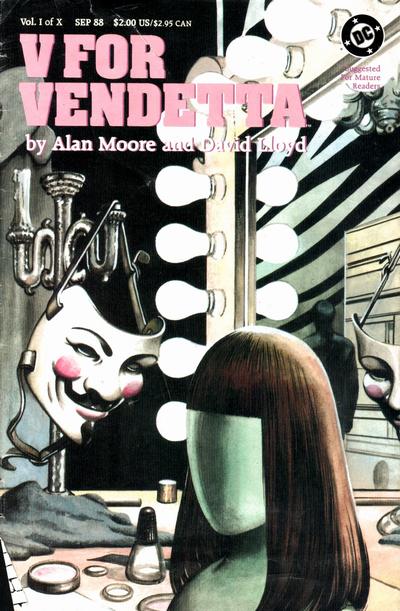

Absolute V for Vendetta, Books I-V (DC Comics, 2009)

Like Alan Moore’s “Marvelman,” V for Vendetta began as a serialized strip in 1982 in the pages of Warrior #1, and when Moore pulled away from that magazine, he left an unfinished story (with a couple of additional chapters already drawn by David Lloyd, ready to print if they ever found a new home), and surely more than a few disappointed readers. Those readers would have to wait six more years before V would return, and Moore’s story would reach its conclusion.

Even when it did return in 1988, thanks to Moore’s then-amicable relationship with DC Comics, it wasn’t the same story that began in those early issues of Warrior. It may have been the same plot, and the same characters, and the same dialogue and all of those things may have been reprinted in the first six-and-a-half issues of DC’s V for Vendetta comic book series but while the original strips were in black and white, the DC reprintings were presented with a haunting watercolor palette.

Reportedly, the DC coloring was supervised by artist David Lloyd himself, with much of it done by Steve Whitaker and Siobhan Dodds in washed-out hues that looked unlike anything else coming out from mainstream comics at the time. But V for Vendetta in color is fundamentally different than V for Vendetta in black and white. So the strip changed when it returned. And that’s worth talking about.

I suppose I should pause to provide a few of the major plot details from the story, for those who haven’t yet fully jumped into the participatory nature of The Great Alan Moore Reread. Basically, the first five issues of V for Vendetta, as reprinted by DC, and as originally published in Warrior, present a dystopian near-future (of 1997!) in which much of the world has been devastated by nuclear war, and Britain, still-standing, uses its Orwellian government to keep the populace under its thumb. The character of V is a kind of swashbuckling anarchist with what seems to be a quite specific revenge scheme against former tormentors of his. Young Evey Hammond, whom V rescues in the opening issue, becomes a convenient tool for V to explain everything to the reader, but also plays a major role in the story, as V’s naïve assistant, and, later, as something far more important.

It has an intentionally retro-pulp feel to it it’s not a near-futurescape that looks anything like the high-tech neon grunge of Blade Runner, for example because it was meant to be Warrior’s counterpart to David Lloyd’s previous gig at Marvel UK, a strip called “Night Raven” about a gun-toting vigilante. In a text piece from Warrior #17, Moore recounts that his original idea was to do a riff on that kind of series, with a character he would call “Vendetta,” set in a realistic 1930’s gangster world. Lloyd’s reply sabotaged those plans. Moore writes, “His response was that he was sick to the back teeth of doing good solid research and if he was called upon to draw one more ’28 model Duesenberg he’d eat his arm. This presented a serious problem.”

Luckily, the same tone could be applied to a dystopian strip, set in a bleak, concrete and shadows near-future. No research required.

And maybe I’m spoiled because I first met V and Evey in the pages of stumbled-across copies of Warrior, but David Lloyd’s black and white art is substantially different than the colorized version. Yes, I know this is always true, and I know I complained about the color problems with Marvelman as well, but it’s even more troublesome with V for Vendetta. Because David Lloyd drew the early V for Vendetta installments without holding lines. He slid away from that style a bit, even before his departure from Warrior, well before the color came in with the DC reprints, but in those early Warrior issues, Lloyd’s visual style is all hard contrasts.

Solid blacks against solid whites (or subtle yellowish-tans, in my weathered copies of the magazine). The lack of holding lines meant that when figures overlapped with backgrounds, with each other they would lap together, creating gorgeous patterns of lights and darks. The word balloons didn’t have holding lines either, so they would also blend into the shapes around them. Lloyd somehow managed to pull off the style, in pure black and white, without making the panels difficult to read, even though he completely rejected the typical comic book rendering styles to show the thin-line external shapes of figures. It was a spectacular feat.

In color, even with moody watercolors in blues and yellows and browns (aka, the very stuff that would later form the basis of the Vertigo coloring palette in the early 1990s), V for Vendetta loses its harsh edges, and loses its patterning, and loses some of its thematic substance. The Warrior version of the story, colorless, is a blade to your throat, and the sound of jackboots in the distance. The DC version, even with what would normally be considered really well-done colors, is a dreamy fable with a few sharpened teeth.

This reread simply reminded me of how much has been lost in the colorization, which, by the way, is apparently David Lloyd’s preferred presentation. He says he always wanted it to be in color. (Though his artistic style in the opening chapters strongly suggests otherwise.)

Let’s get past the color then. This is, after all, supposed to be about Alan Moore.

So what do the first five issues of V for Vendetta offer, from a looking-back-at-Alan-Moore perspective?

Plenty!

While Marvelman was Moore’s early and effective version of superhero deconstruction, V for Vendetta is his first formalistic masterpiece. It’s still genre-bound, fully embracing the dystopian tradition of George Orwell (moreso than Huxley or Zamyatin), and crafting a revenge tragedy within those confines. But it is also structurally ambitious. Ironically, for a comic about an anarchist, it is one of Moore’s most orderly constructions.

Perhaps that structuralism stems from Moore’s attempts to make V for Vendetta both novelistic and musical, two highly-structure-friendly forms. It’s also notable that, at the request of David Lloyd, Moore’s doesn’t use any narrative captions in the series. There are a few examples of voice-over monologue later in the series, but Moore largely abandons any kind of narration in V for Vendetta. It’s a comic about visuals and dialogue, pretty much the convention in today’s comics, but quite rare in the 1980s. Without narrative captions, and with a good writer, plot information and thematic passages lie within the patterns of the story.

The most obvious example is the repetition of the letter “v” itself, from the title through the protagonist’s name (note: the character V has no identity beyond the name and the Guy Fawkes mask, and what we later learn about his presumed past, and he remains anonymous, and faceless throughout), through every chapter title, from “Villain,” to “The Voice,” to “Video,” to “The Vacation.” The most prominent female character is “Evey,” and the whole structure of Act I and Act II of the overall story is predicated on vengeance.

Holding up two fingers signifies the number 2, of course, and V for Vendetta is filled with doublings and contrasting dualities. I’ll get more into that next time, but I’ll mention here (since I seem obsessed with it) that it’s yet another reason why the story suffers with the addition of coloring. The black and white becomes a faded rainbow.

And the “v” sign in Great Britain has even deeper connotations than it does in the United States. The Winston Churchill “V for Victory” sign reputedly goes back to Henry V and even further, as a sign from the English archers to signify they have not lost their fingers, they have not lost the battle. And the victory hand sign, reversed, is an act of defiance. Doubling, dualities, embedded throughout the v-motif of Moore and Lloyd’s work.

Other patterns and recursions in the comic are less ambitious how could they help but be? but even something as simple as using elegant foreshadowing (like when V plucks one of his white roses in Chapter 5 and then we don’t learn its meaning until Chapter 9) is structurally ambitious for the time, when most comic books were written month-to-month, without any kind of longform narrative plan. The novelistic approach to comics was far from the norm in 1982, but Moore committed to it right from the start in V for Vendetta.

Even V’s “Shadow Gallery,” his bunker full of the relics of a disappeared culture (jukeboxes and paintings, Dickens novels and theatrical costumes), is packed with symbolic power. It’s a safehouse of the protected past, but at what price? And is V “collecting” Evey the way he has collected other beautiful, forgotten things?

That’s one of the most impressive feats of V for Vendetta, evident within the first five collected issues, certainly. It’s all about doubling and dualities, but it’s not a clear case of good and evil. V, who seems to be a hero, saving Evey from sure violence in the opening chapter, is not just a representative of a victim who deserves his revenge. He may be that, but his means are beyond extreme, and he is hardly sympathetic. We never see his face, we always see his demonic grinning façade, and his ultimate goals clearly go far beyond what would make sense to anyone reasonable.

There’s a madness underlying V, and not a movie-madness where the hero will learn to love or learn to live, but a true sense of instability and insanity that goes beyond rationalism. He is a force of anarchy in an overly-ordered world that is bland and bleak and without hope. But yet he acts with surgical precision, and Rube Goldberg machinations, and his anarchy and insanity double back on themselves to indicate someone without any traditional morality.

Is this even a moral comic? Does it posit any answers in that regard? Does it matter, if the structural ambitious and the narrative execution is so impressive?

We can’t answer those big questions until we get to the end of the story. Original readers of V for Vendetta waited half a decade. We’ll conclude our exploration in one week.

Until then, offer some thoughts of your own.

NEXT TIME: V for Vendetta Part 2

Tim Callahan writes about comics for Tor.com, Comic Book Resources, and Back Issue magazine. Follow him on Twitter.